Part 2

Waiting on a Train

Contemporary Physical Implications of High Speed Rail

Beginning

with Japan in the 1960s, carried on by France and Germany throughout the 70s,

80s, and 90s, and implemented more recently by Spain, China, and South Korea, high-speed

rail (HSR) has had profound physical implications on the contemporary city.

This section unveils how high-speed rail has contributed to the physical form

of cities at multiple scales, starting with that of the nation and ending with that

of the human.

2.1

Supernation//Nation

2.1.1

The Evolution of Representations of Distance and Time

Part

1 of

Riding the Rails ended with a

discussion of nineteenth century representation techniques specific to a

shrinking world, so it seems appropriate to begin Part 2 with a discussion of twentieth

century techniques and a personal foray into twenty-first century techniques.

The "annihilation of space” was a common expression used in the nineteenth century to conceptualize the changes being wrought by the railroad. Though commonly attributed to Karl Marx, Alexander Pope first used the expression in a poem, lamenting, “Ye Gods! Annihilate but space and time, And make two lovers happy.” Throughout the twentieth century writers and philosophers began to describe the social, economic, and spatial implications of new mobility technologies: not just trains, but aircraft and communications technologies as well. Donald Janelle first coined the term “time-space convergence” to discuss the ways in which different places around the world were actually closer to each other than they used to be—maybe not as measured in miles, but certainly in minutes. The impetus for this idea was borrowed from Einstein’s theories on relativity in the mid-twentieth century, which challenged the traditional Newtonian idea that position and space are absolute: In modern physics and philosophy, distance is no longer considered a universally valid parameter for describing the relationship between points, events, or particles in space. For the physicist to describe such relationships, it is necessary that he view them in time-space and that he knows their positions, their velocities, and the direction in which they are moving.

Janelle’s work on time-space convergence suggests that “four inextricably linked dimensions (three dimensions of space and one of time)”, means that we should no longer think of time and space as separate phenomena, but instead as a unified concept “time-space.”

Later in the late twentieth century, social philosopher and geographer David Harvey coined the term "time-space compression" to capture this sense of overwhelming change in the very dimensions of space and time. Although his work focuses on economics and capitalism, he produced a map to highlight the historical eras and their mobility technologies that have contributed to time-space compression. The earth is shown growing proportionally smaller as speeds increase, and the map optimistically treats time-space compression evenly across the globe. For example, in this map Africa is being pulled as closely to America as Europe in units of time. Yet we know in practice that most places in Africa remain quite remote, geographically and temporally, and certainly much further than Europe from America. While the world may be shrinking, it isn’t shrinking uniformly.

While the world may be shrinking, it isn’t shrinking uniformly.

Ideas such as time-space convergence and time-space compression challenge the hegemony of geographic distance in cartography, though cartographers have only just begun to experiment with maps that privilege relativity over absolute distance. One example of such a representation is a form of cartogram often called an anamorphic map. A cartogram is a type of map in which some variable distorts the areas (area cartograms) or distances (distance cartograms) of the map. This distortion of area or distance is intended to convey important thematic variables of concern, such as time-space compression.

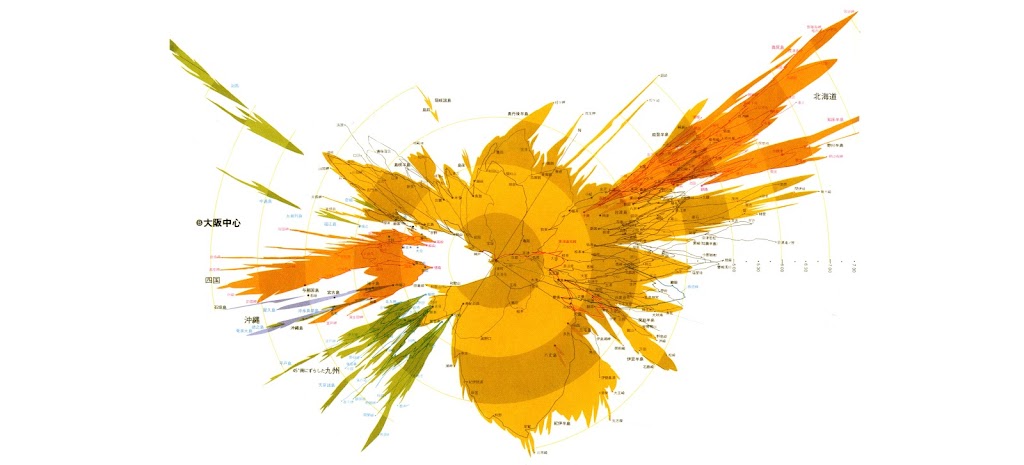

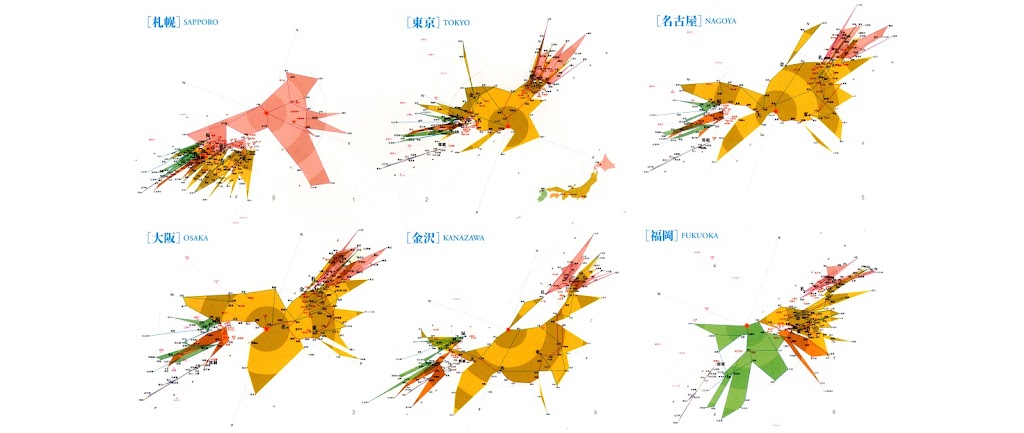

Japanese graphic artist Kohei Sugiura produced an early example of anamorphic maps dealing with time-space compression in the late 1960s. As in the nineteenth century, Sugiura’s topic for studying the spatial implications of time-space compression is the railroad: this time the technologically superior Shinkansen in Japan. He created maps and diagrams at many different scales, from the city to the globe, but the most popular diagram is that of the distortion of the Japanese archipelago after the introduction of the Shinkansen in 1960.

Suguira’s maps are rather violent, suggesting an upheaval of land that is egocentrically reorganized around a fixed point. The familiar shape of the archipelago is warped and compressed, sculpted into the silhouette of an alien flower. When one presupposes absolute distance as a given, the map is simply a scaled tracing of the ground condition and, therefore, is naturally static. But when relative distance is the presupposition, the ground plane is twisted, skewed, and warped to reflect travel time from a particular starting point.

Simplified time-space maps of various Japanese cities. Source: Kohei Suguira.

While

the Shinkansen anamorphic maps were laboriously created by hand, continuous

developments in technology have made the creation of these cartograms much

easier. In the example below, created by the author, the country of Spain is

rendered through the lens of a series of transportation modes: a typical car

journey at 9:00AM on a Monday in 2015, a typical AVE high-speed train journey

in 2015, and a typical AVE high-speed train journey in 2020 (post HSR network

completion). Each map is warped and distorted based on time distance to major

cities using a specific mode of transportation. [Or rather, each map more

accurately depicts relative distances based on time-space compression.]

[[slider id="211"]]

For example, in the case of Spain, the hub-and-spoke organization of the rail network pulls all connected cities closer to the hub, which is Madrid. But because there is no direct high-speed connection between, say, Barcelona and Bilbao, those cities are not closer to each other in relative space. Madrid is the beneficiary of both connections in terms of time-space, and logic would also suggest it as the ultimate economic beneficiary as well. Geography, and position within the railroad network, grants certain temporal, as well as economic and political, advantages.

Through these anamorphic representations, the explicit advantage of one position in relative space over another highlights an important feature of the contemporary landscape: an increasing disparity in the difficulty of overcoming what David Harvey has termed the ‘friction of space.’ When construction on the Galicean high-speed network is complete, Madrid will be just over two hours from Ourense. Yet Porto, in Portugal, which is similar in absolute distance from Madrid, will remain five to six hours from Madrid by car, and a shocking twenty-one hours by train. From the perspective of Madrid, Porto is trapped in space whereas Ourense is unlocked, the friction of space reduced to the cost of a ticket.

2.2

Nation//City & City//City

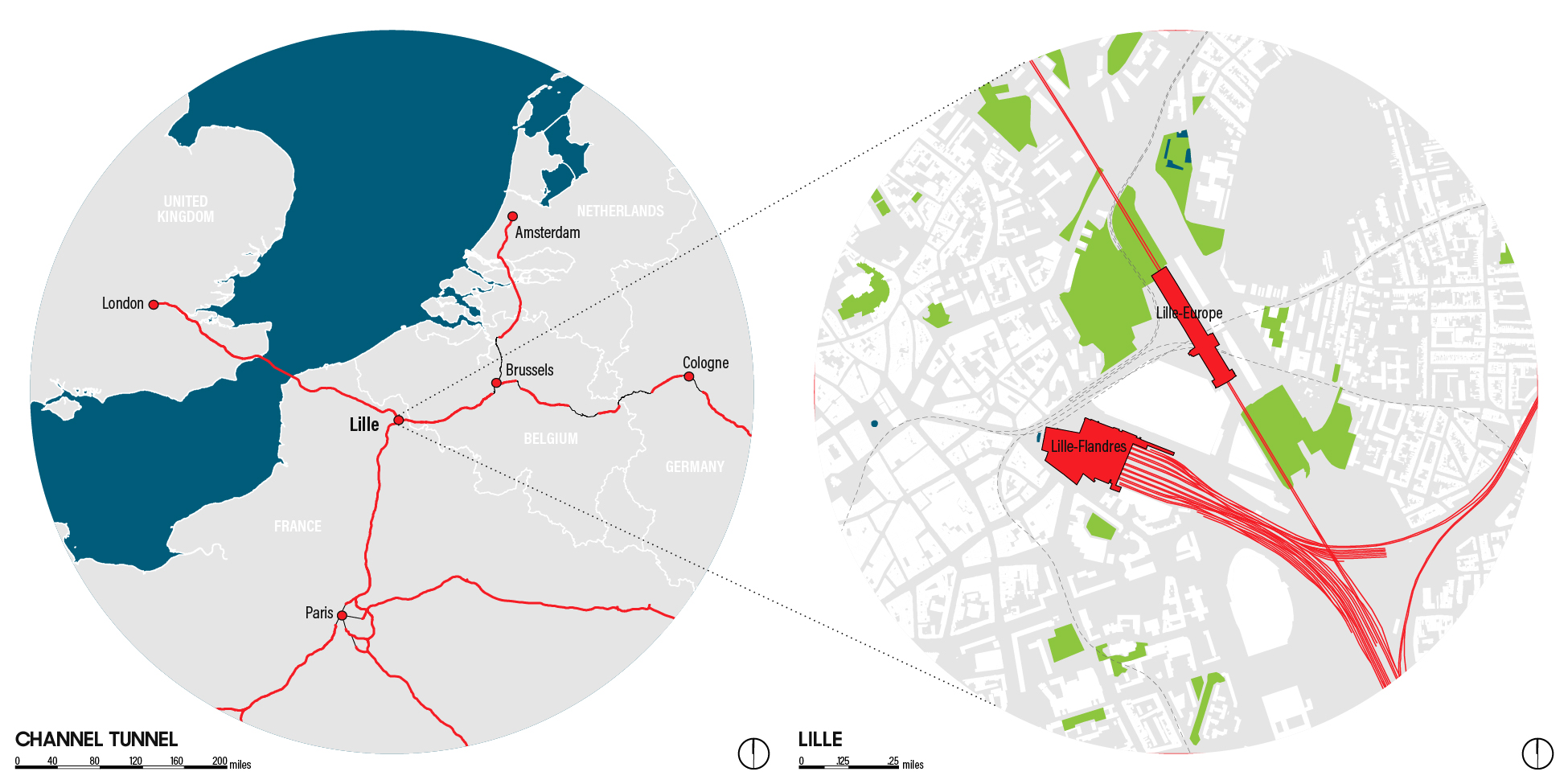

In

2015, high-speed rail was in operation, or under construction, in twenty countries

across the world. These countries are shown below using the best UTM projection

for each location, with a common scale for comparison.

[[gallery id="221"]]

A

variety of economic, cultural, geographic, topographic, and political

conditions influence the organization of these systems. Although each system is

unique, the following network typologies have emerged over time.

In

almost all cases, HSR networks reproduce at least some amount of the pre-existing

conventional-rail network. Tom Zoellner notes the fundamental influence of nineteenth-century

railroad networks, declaring:

Under the skin of modernity lies a skeleton

of railroad tracks.

Both physically and in terms of persistent cultural

and political development trends, the conventional railroad “skeleton” of the nineteenth

century shapes the HSR networks of the twenty-first century in several

important ways.

Under the skin of modernity lies a skeleton of railroad tracks.

Tom Zoellner

Firstly, it is much more difficult today to implement brand new national or territorial scale

infrastructure corridors than it was 200 years ago. Public sentiment towards eminent domain or land

condemnation towards large-scale transportation projects has soured, and more stringent labor

regulations and the rising cost of materials makes these projects challenging. There are a variety

of other factors as well, such as: lack of political will or political disagreement towards system

design or implementation, strong anti-rail lobbyists from competing transportation modes, NIMBYism,

lengthy processes for environmental reviews, and the lack of availability of capital to name a few.

Therefore, expanding existing conventional-rail rights-of-way is usually easier and more expedient

than forging new connections through private lands, especially in developed urban areas.

Secondly,

pre-existing conventional systems typically have already linked all the

important economic, political, and cultural centers in a given country. Any HSR

route will travel along the same, or similar, path as the conventional network.

(In fact, the existence of an important conventional rail connection was usually

a historically important factor in the ability of one city to thrive over

another in the same region.) There are important exceptions to this

observation, however, such as in Germany and France.

Finally, geographical constraints are the same now as in the past: high-speed trains are most efficient over flat terrain, as were their steam and diesel forbearers. Mountainous terrain requires more expensive civil engineering designs, including tunnels, bridges, and viaducts to create a straight and even rail bed for the network. To the extent possible, high-speed networks tend to avoid geographically challenging areas just as the conventional network designs of the nineteenth century.

These new high-speed networks establish a new operative scale for designers, conflating the traditional scale of the city and the region or even nation.

Despite these hurdles, the introduction of contemporary HSR networks do more than just reproduce the routes of the past: these high-speed networks establish a new operative scale for designers, conflating the traditional scale of the city and the region or even nation. In order to understand this emerging scale of design, we need to understand the historical development of both the conventional and high-speed rail networks in several cultural contexts. Below is a brief history of the development of conventional and high-speed rail networks in Japan, France, Germany, and China.

2.2.1

Nation//City: Japan

The

first country to develop a true high-speed rail network was Japan in 1964. On

October 1st, nine days before the Olympic Games were scheduled to begin in

Tokyo, the first Shinkansen trains departed for Osaka and Tokyo to the fanfare

of hundreds of citizens and visitors. To the awe of the world, these trains

would arrive at their destinations a mere four hours later. Only the day before

the same journey would have taken seven hours. In the summer of 2014, my own

journey along this route took only two hours and fifty-five minutes, with a top

speed of 300km per hour. Japan has dramatically compressed the relative distance

of major urban areas.

As the pioneers of HSR technology, the Japanese still set the bar for the safest, most timely, and most efficient train service in the world. Since 1964, an estimated 5.6 billion passenger trips have been made on the train without a single fatality. Delays are within one minute on average, even during rain and snow. The network has earthquake-sensing technology, which halts the train in the early stages of an event. During rush hours, the network is capable of running one train every three minutes on each line.

In the last fifty years the Shinkansen has expanded outward from the original Tokyo-Osaka connection on the Tokaido corridor. To date there are an additional seven high-speed routes, including two “mini-Shinkansen” that branch off the Tohoku corridor in the north. Three additional Shinkansen routes are under construction, extending the system to the tips of the Japanese archipelago. In 2015 approximately 1,487 miles of track were operational.

Though Japan wasn’t one of the first countries to adopt conventional rail in the nineteenth century, the geography and population distribution on the archipelago were, and are, ideal for train travel. The islands are nearly 2,000 miles long in total, and relatively narrow: Honshu Island, the major landmass, varies from 31 to 143 miles wide. The mountainous geography further narrows the inhabitable area of the islands, gathering most of the population to the coasts. Japanese historian Nobutaka Ike describes the region in the late nineteenth century, writing: [B]y the time the Western impact began to be felt in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Japanese economic system was already sufficiently developed to be able to sustain as well as profit from a railroad system. By this time, too, the potentialities of an increasing passenger traffic were favorable, since Japan had a high population density when compared to the countries of contemporary Europe. This then forms the background against which the development of the railroads should be viewed.

The

Japanese welcomed the new technology from Europe, but not without a few caveats,

as Nobukata describes:

In 1867, an official of the Tokugawa government

actually gave permission to...an American diplomatic official to build a line

between [Tokyo] and Yokohama. But this [permission] was revoked, over the

protests of the American Minister, by the new Meiji government, which was

determined that railroads be built by Japanese and not foreigners.

As such,

construction of this first line was slow, but within ten years the Japanese

were constructing and operating their own railroads with little Western

involvement. Although the idea of the railroad was planted there by

Westerners, the Japanese alone were the architects, engineers, and operators

of their own railroad from the very beginning. This knowledge goes a long way

towards understanding how the Shinkansen has become a national symbol of Japan.

After

construction of the first line, the government opened up construction of

railroads to private development. While this strategy had the effect of

encouraging development, it also created problems. For example, investors were

naturally interested in maximizing profits, and the most profitable scenarios

for railroad construction were in areas of either high population density or

low construction costs. This left vast territories without the hope for

railroad service through private development. As in America, privately

developed routes were discontinuous and long distance freight charges were

difficult to estimate if the route involved multiple carriers. Although Japan

had adopted a common narrow gauge design for the tracks, other design elements

such as platform height and width were not standardized. Early private

efficiencies on the local scale resulted in regional obstacles to good rail

travel.

Some lines zigzagged from one town to another or looped in a huge half-circle through several towns rather than merely linking larger cities.

Nobutaka

This was frustrating for passengers and the military alike, which increased support for nationalization of the railway companies. In 1904, a bill was passed allowing the government to purchase private railroads, and by 1910 the government controlled 90% of all railroads in Japan. Growth of the network continued under government ownership, especially after the 1922 Railway Construction Law. Importantly, this growth was in response to local constituencies and politicians’ concerns, which Nobutaka describes, writing: [I]t led to a situation where some lines zigzagged from one town to another or looped in a huge half-circle through several towns rather than merely linking larger cities.

It is in this landscape of national railroad ownership and operation, with a high degree of catering to local constituencies with a relatively narrow gauge track, that the idea for a high-speed train came into the Japanese imagination. In the 1930s, the Japanese colonial empire extended to Korea, Manchuria, Taiwan, parts of China, Indonesia and Polynesia. A political propaganda scheme in alignment with Japanese imperialism and anti-western sentiment emerged called the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” In this political hallucination, the Japanese would be the elite leaders of a bloc of Asian countries free from Western interference.

The key to this imagined future, physically and in the collective Japanese imagination, was the dangan ressha (弾丸列車): literally translated to “bullet train” (in reference to the envisioned speed of the train, but also the colonial and world wars of the time). The dangan ressha would link Tokyo, the Japanese political, economic, and cultural capital, to all the nations of the Co-Prosperity Sphere at the highest speeds imaginable for rail transportation. It would catalyze Japanese colonization and resource development throughout the territories, creating a connected Asian transportation loop. A quote from the PWR article above captures the excitement of the age: Imagine, we are on our way’ we say with bag in hand, boarding a train that goes to Shimonoseki, Keijo [Seoul], Mukden [Shenyang], Beijing, Canton [Guangzhou], Hanoi, Saigon [Ho Chi Minh City], Bangkok, and finally, without ever having gotten off, we arrive in Shonan [Singapore]. Wouldn’t that be wonderful...and yet, this wonderful dream could very possibly come true in our lifetimes.

It was not the ship, nor the plane, nor the automobile, but the high-speed train that became the shared imaginary of modernization in Japan.

It was not the ship, nor the plane, nor the automobile, but the high-speed train that became the shared imaginary of modernization in Japan. World War II halted development of the routes, though land was purchased and a few tunnels even constructed before Japanese efforts were diverted to the war. Post-war reconstruction followed, further delaying the development of the dangan ressha. The idea was resurrected before the Tokyo Olympic Games of 1964, this time under the moniker of Shinkansen (新幹線), which translates to “new main network” or “new trunk line.” This name alludes to the choice of gauge for the new network, which would be designed at the international standard gauge instead of the narrow gauge of the local routes. This technical decision ensured that the Shinkansen would never integrate with the local routes, operating at a scale between the city and the nation without entering into local scale.

"The (Shinkansen) project just made all the [connecting] cities part of Tokyo."

Takashi Hara

While the post-war Shinkansen plans leverage the imagination of the dangan ressha, the scope is more national in focus. Instead of connecting Tokyo to its colonies, the Shinkansen would connect Tokyo with the hinterlands of its home islands. According to a recent Guardian article: All previous railways were designed to serve regions. The purpose of the Tokaido Shinkansen, true to its name, was to bring people to the capital. Takashi Hara, an expert on Japanese railroads, has stated: The purpose was to connect regional areas to Tokyo...and that led to the current situation of a national Shinkansen network, which completely changed the face of Japan. Travel times were shortened and vibration was alleviated, making it possible for more convenient business and pleasure trips, but I have to say that the project just made all the [connecting] cities part of Tokyo.

[[slider id="221"]]

These

quotes suggest that the Shinkansen has expanded the boundaries of the city into

the nation itself, collapsing the scale of the territory and conflating the

traditional scales of nation and city. This phenomenon is seen in other

examples throughout the research, but it should be noted that this condition of

“nation as mega-city” is particularly suited to Japan’s culture, geography, and

business practices. For example, in the traditional paternal culture Japanese

corporations often pay for employees’ commuting costs. Since the Shinkansen

makes the suburbs temporally proximate to Tokyo, and cost of the ticket isn’t a

primary factor, the extent of the city is expanded. The nation itself is

relatively small, fitting easily in one time zone. Socially and culturally, the

notion of homogeneity is perceived as positive. Journalist Allison Hight states:

There is little emphasis placed on the individual, and people instead derive

their worth and usefulness from their ability to work as part of a team.

In

short, the development of Japan’s rail network exhibits the market forces of the

private sector, and the inclusiveness of the public sector. While the

Shinkansen makes the collapse of "nation-space" into urban space

possible, the phenomena is heavily reinforced by the Japanese geo-cultural

tendencies. “If you look closely, you will notice that the most dramatic change

enveloping Tokyo is in the kinds of people found here. This is a natural and

inevitable result of the extension of modern transportation,” says Tayama Katai

in

Thirty Years in Tokyo. The

Shinkansen changed the face of Tokyo and reorganized space on the island

nation.

2.2.2

Nation//City: France

Although

the historical conditions were quite different, the development of the French

Train

a Grande Vitesse

(TGV) high-speed rail network has much in common with the

Japanese Shinkansen network. Both use a hub-and-spoke diagram to connect

second-tier cities to a populous and expansive national capital. Both employ

dedicated high-speed passenger networks, though France does have some amount of

blended access in urban station approaches and at route branches near the end

of the lines, and the TGVs are equipped to travel on local routes at slower

speeds. Both networks achieve a substantial collapse of the scale of the

territory and conflation of the traditional operative design scales of nation

and city. Unlike Japan though, France’s development has nearly always been

centrally planned by the government in some form, and the Shinkansen was an

important motivator for the French in the creation of their own TGV.

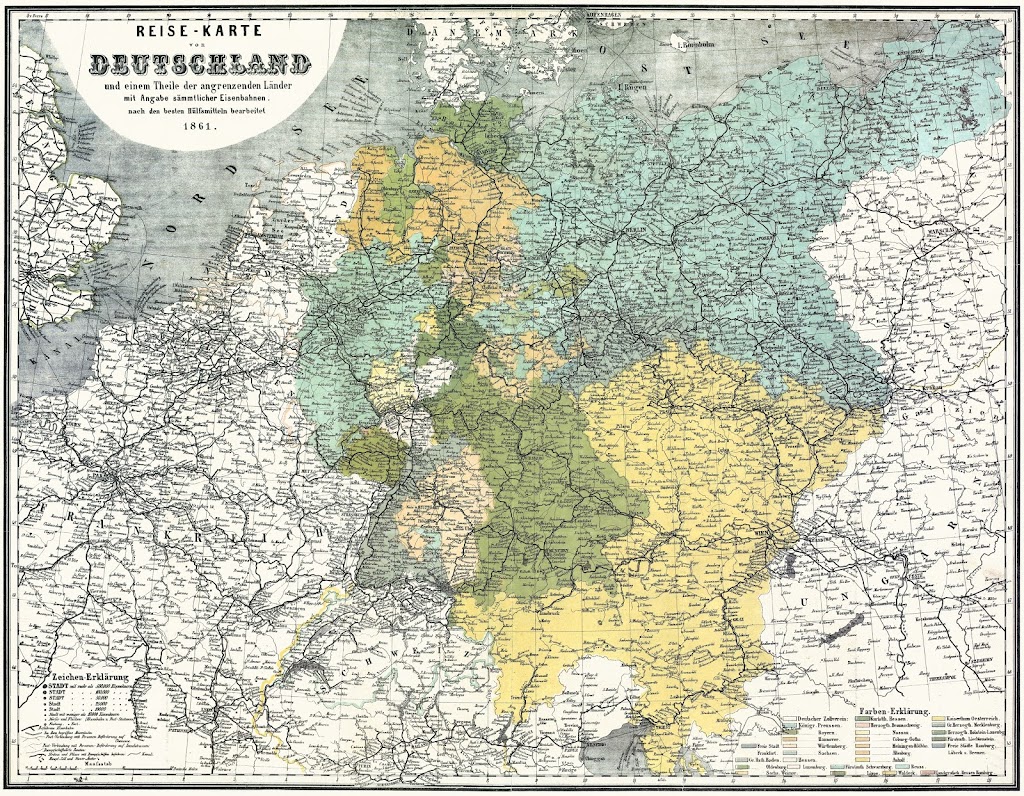

In

early-nineteenth-century Europe, railroad development was thriving in

industrialized and laissez-faire economies such as in the UK, Belgium, and

Prussia (Germany). But in France, conditions for private development of

railroads were not favorable. At the time, France was less industrialized than

her neighbors, and lacked the important natural resources of coal and iron ore

that propelled the UK’s industrial revolution and railroad construction. Iron

production was slow also, which further hindered industrial scale track

construction. France had ample natural waterways too and had invested heavily

in the construction of canals, and the water transportation industry lobbied

against the new railroads. The country was still recovering from the Napoleonic

Wars (1803–1815), which shifted focus to the reconstruction of important

cities. Additionally, the lack of a strong unified national government caused

lengthy delays towards developing a national policy for rail development.

In the early years a few lines gained the required capital and approvals for operation. Permission was given by royal decree in 1827 for construction of a line from Saint-Etienne to Andrezieux for goods, extended to Lyon in 1830 for passengers. The first dedicated passenger train was opened in 1837, from Paris to St. Germain. It was an enormous success, carrying 18,000 passengers on its inaugural day of service. Despite these few lines (totaling only 354 miles) operating in the early years, a national effort towards developing a railroad network wasn’t really begun until a railroad law was passed in 1842.

This law conditioned the development of the railroad network through the following parameters:

- The state would acquire the necessary right-of-way, design the railroad through the Ponts et Chaussees (a sort of national engineering department), and prepare the roadbed, bridges and tunnels.

- Private developers would supply the tracks, rolling stock, stations, and operate the lines.

- Long term leases were granted: 37 years to begin, later extended to 99 years.

This

arrangement eased the way for private development of railroads, but the

national government determined which routes were given consideration. So it

comes as no surprise that all major routes radiated from Paris, France's

political, cultural, and economic capital. The small companies that undertook

initial construction of the lines were eventually bought and consolidated into

six major rail monopolies: Nord, Est, Ouest, Paris-Orleans,

Paris-Lyon-Mediterranee, and Midi. These companies built grand terminal stations

in Paris, but did not connect with each other and no two lines operated out of

the same station. Their routes into Paris did not merge with each other,

remaining separate and terminating at what was then the periphery of the city.

This urban arrangement of stations can be seen in many cities, including

London, Vienna, and contemporary applications in Beijing and Shanghai. (This

development pattern is an important reason historic train stations tend to be

typologically designed as terminal stations, whereas high-speed rail has

largely invented the contemporary through station.)

This was not an efficient system. For passengers whose destination was not Paris, a lengthy transfer across town by foot or hired carriage was always required. Goods had to be offloaded and transported similarly to other stations for further destinations. East-west movement across the country was still difficult, requiring an unnecessary trip into Paris. At this time, the conventional railroad network did a good job of connecting cities to Paris, but a rather poor job of connecting second-tier cities to each other. The network design fragmented the country into wedges, each defined and monopolized by private railroad operator.

Although

successful and integral to the movement of goods and people through the

country, all the major railroad companies were operating at a deficit in the

early twentieth century. It was determined that the largest railroad monopolies

would be nationalized in 1937 into the Societe national des chemins de fer

francais (SNCF), a public-private entity. World War II brought occupation by

the Germans and significant destruction of the railroad system, requiring SNCF

to cut service to secondary lines after WWII in an effort to stem financial

losses and improve service on the primary network.

Paris has always been the central location of political, economic, and demographic power within France, which produced and was reinforced by the nineteenth-century spoke-and-hub organization of the railroad. However, certain events in the mid twentieth century challenged the traditional dominance of Paris and encouraged reflection on the role of the French territory. In 1947 geographer and professor Jean-Francois Gravier published an important and influential study titled “Paris et le desert francais” (“Paris and the French Desert”), which highlighted the disparities between rural France and the capital. He cautioned that, “Two-thirds of France is slowly dying” and encouraged economists and politicians to address the strong imbalances between Paris and the country at large. Later, an exode rurale between 1952–1962 of rural to urban migration was a further cause of concern to politicians, geographers, and economists alike. Jacob Meunier cites: By 1968, some twelve million French men and women had migrated from the country to the city. France, 46% rural immediately after the war, was only 34% rural by the end of 1960s.

This concern led to a large scale program of incentives for industrial, demographic, and cultural decentralization along with agricultural modernization overseen by a new and powerful government organization, the Delegation interministerielle a l'amenagement du territoire et a l'attractivite regionale (DATAR), which still exists today under a slightly different acronym. DATAR’s strategy to address the powerful hegemony of Paris was to designate eight regional capitals for targeted development: Lille/Roubaix Tourcoing, Nancy/Metz/Thionville, Strasbourg, Lyon/Saint Etienne/Grenoble, Marseille/Aix-en-Provence/Delta du Rhone, Toulouse, Bordeaux, and Nantes/Saint Nazaire. Along with plans to incentivize demographic, industrial, and economic growth, DATAR advocated for transportation development within these metropoles (usually highways) and would often find itself naturally at odds with the SNCF, which was cutting service to secondary lines in these areas. Furthermore, DATAR supported another high-speed rail technology under development by Jean Bertin at the time called the Aerotrain.

Within

this condition of existing tension between the urban (mainly Paris) and the

rural, and between SNCF and DATAR, the Shinkansen made its inaugural run from

Tokyo to Osaka in Japan. Like Germany and the United States and, indeed, most

countries at the time, France was inspired by the Shinkansen in the 1960s and

unsettled by the oil crisis of the 1970s. SNCF began research into a high-speed

rail system for France and soon developed the technology for a TGV high-speed train compatible with

both existing conventional lines

and a new network of

Lignes a Grande Vitesse (LGV) high-speed lines. The first

route from Paris to Lyon, also known as the LGV Sud-Est, was wildly successful

and led to an expansion of the network to the south (LGV Rhone-Alpes and LGV

Mediterranee), and new lines in the west (LGV Atlantique), north (LGV Nord),

and east (LGV Est).

The LGV network doesn’t trace the primary conventional routes exactly, but it does establish a similar spoke-and-hub network that recreates the inherent difficulties of the conventional system. For example, the LGV Atlantique departs from Gare Montparnasse to Le Mans and Tours, the LGV Nord departs from Gare du Nord to Lille, and the LGV Est departs from Gare l’Est to Strasbourg. TGVs terminate in Paris at the historic conventional stations, so as it was throughout history, it’s easy to get to Paris but harder to simply go through Paris. The separate lines functionally create “wedges” of TGV service extending from Paris into the hinterlands, but do little to connect the regions to each other. Despite the creation of DATAR and its advocation for decentralization, east-west movement across the country remains difficult and usually requires a trip through Paris. Furthermore, investment in the LGV network has come with certain costs for the conventional network.

The separate lines create “wedges” of TGV service extending from Paris into the hinterland, but do little to connect the regions to each other.

Michael

Bunn states:

The thirty years of the TGV in public service have been a

fabulous success, with 220 towns served, journey times reduced and a very high

level of reliability and passenger satisfaction. However, there is no doubt

that the development of the TGV network has been at the expense of investment

in the classic [network].

Given SNCF’s policy of privileging main network

service over secondary lines/local interests to maximize profit, the

development of the network in this way is not surprising. Still, DATAR and

local interests have had some effect on the quantity and location of TGV

stations, if not the design of the overall network. One example is the case of

the first LGV from Paris to Lyon.

Diagrams developed by SNCF in June, 1970 in support of their chosen route from Paris to Lyon. (Notice the blended service at the approach to both cities.) Source: Projet de la Ligne a Grande Vitesse Paris-Lyon.

During

initial route planning in 1973 SNCF created several alternatives. Option one

largely followed the existing conventional network to Lyon, establishing new

tracks only to Dijon and utilizing the existing quadruple-tracked route from

Dijon to Lyon. The second option was similarly routed through Dijon, though not

parallel the existing route at all times. The third option included new,

dedicated track to Lyon via Troyes and Dijon. The fourth option suggested new,

dedicated track in an almost straight line to Dijon, bypassing Troyes and then

heading south to Lyon. Options five and six called for new high-speed lines

from Paris to a point on the conventional rail network near Dijon, at which

point branch service would accommodate Dijon and trains would continue to Lyon.

Option seven was SNCF’s preferred route (see above), which bypassed Dijon in

order to create a nearly straight-line solution to Lyon. Branch service off the

new line at Aisy and Macon would serve mid-size cities in the Burgundy region,

as well as service to Switzerland and the south of France.

To the dismay of Dijon and DATAR, SNCF prevailed and the preferred option was constructed. It is important to note that intermediate stations at the small cities of Le Creusot and Macon were not intended by SNCF. Instead, these cities were incidentally near the straight-line path from Paris to Lyon, and city stations were only later included at the urging of DATAR and local governments. In order to accommodate these cities, new TGV stations were constructed not at the city centers, but at the city periphery such that the route was deviated as little as possible, and station construction costs were minimized. The French have a term la gare betterave to describe these stations, which translates to “beetfield stations.” This station typology will be discussed further in later sections, but their existence provides a good conclusion for this discussion of France and the conflation of scales: City//Nation, or rather in this case: Paris//Nation. Although SNCF operates some 230 TGV stations, many of them are small, rural gares betteraves with limited service. Only large regional cities have new or renovated city-center stations. Coupled with the national hub-and-spoke organization, the overall effect of the TGV in France is to bypass the region in favor of direct urban to urban connection with Paris.

2.2.3

City//City: Germany

Unlike France and Japan, the German high-speed rail network is not organized around a single primary city. Rather, the organization is polycentric, characterized by the dispersed location of several equally important hubs throughout the country. As previously mentioned, in most instances high-speed rail networks are influenced by the conventional rail development of the nineteenth century. In the case of Germany, however, the rail network is also heavily influenced by persistent cycles of unification and separation, the political/administrative disunity of individual German states (of which there are many), and significant fluctuations of the national borders over time. Railroad development by both state and private developers began before the German Empire was first unified in 1871.

[[time id="223"]]

The first steam railroad was developed between Nuremberg and Fürth in Bavaria in 1847 by a private company that made the pragmatic decision to adopt the UK’s standards for track design for both rail profile (shape of the rail) and gauge (width between rails). Development continued throughout the individual German states using these standards as a model. Surprisingly, even though the system was constructed and operated by individual states and private owners, most of the major cities were linked by the 1890s. Unification of the many German states in 1871 spurred state level consolidation and cooperation among the Lander (individual states) into a comprehensive main network that serviced all of the states. Moreover, private railways continued to develop complementary services in the form of local and secondary lines. By the First World War, the country had established a comprehensive, non-centralized, distributed railway network.

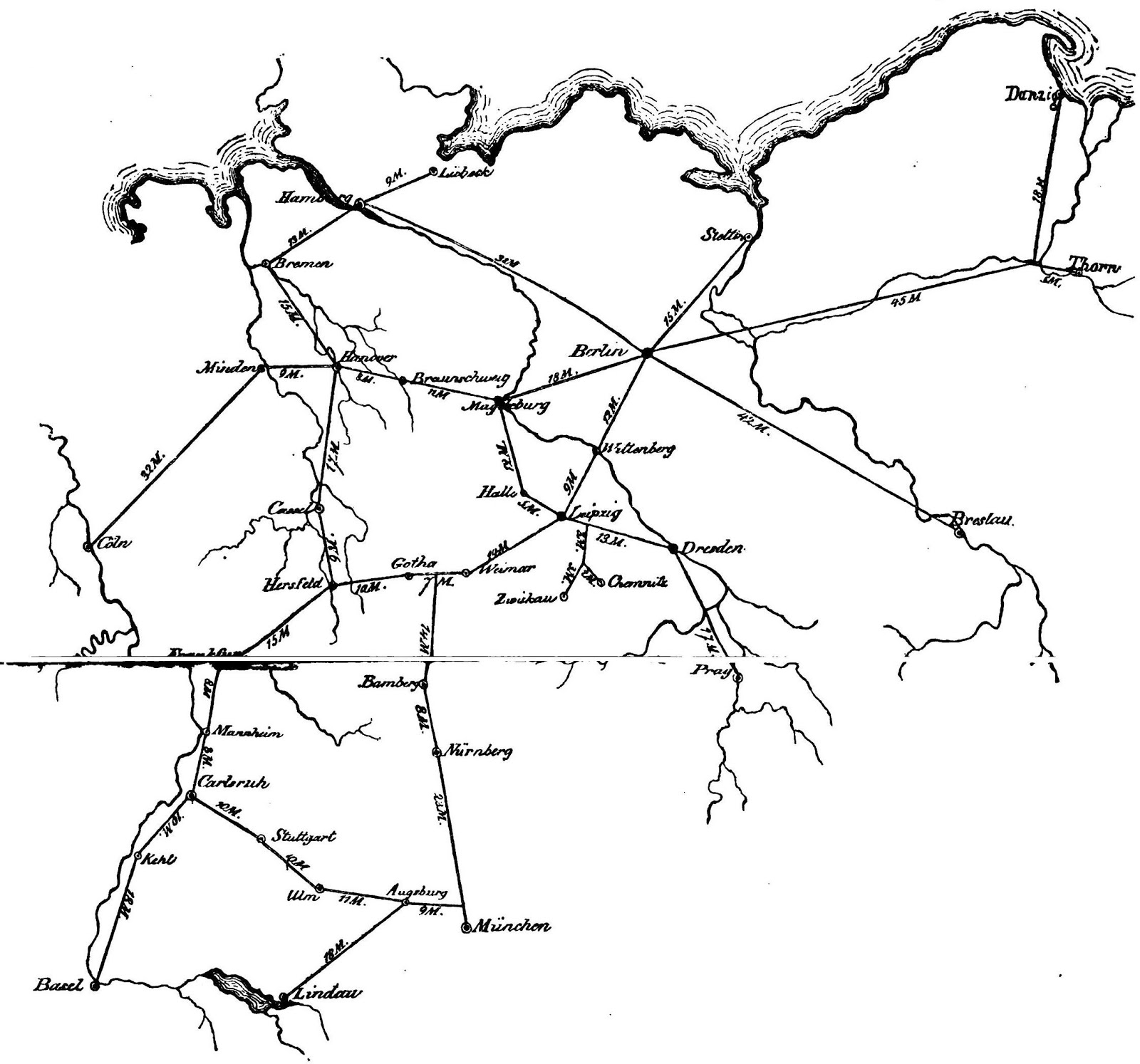

The German economist Frederick List was the first to lobby for a unified national planning

initiative in 1887. In his network proposal, the edges of the country are left vague and

uncertain. The focus instead is on Berlin, the capital, and it’s relationship to the other

important cities in the nation and especially in the northwest. List’s design shares structural

elements of the hub and spoke typology established in France. Berlin is positioned as the hub of

the German Empire, with spokes radiating out to important cities. (Note that in the late nineteenth

century, Berlin is much more centrally located within the boundary of the country than its current

location today.) An important variation is the design of the system in the west, with the inclusion

of circumscribed ring routes connecting cities to each other, as well as to Berlin. This design

recognizes the importance of interdependence among those cities even in the nineteenth century, and

is a prescient glance at the future high-speed network in the twenty-first century.

Germany’s defeat in WWI triggered a political upheaval with important ramifications on the operation and development of the railway. After the war, the individual states would no longer have control of their own lines. Instead, the system was further consolidated into one nationalized system in 1924, called the Deutsche Reichsbahn (German National Railway). The Reichsbahn was organized as a commercial company that would operate to turn a profit, which would largely be used to pay war reparations. The company was a complete success, by some accounts the most successful in the world at the time, and definitively the largest transport company in the world. The backbone of the company was freight transportation. Although the Reichsbahn flourished and was able to undertake modernization projects, locomotive technology standardization, and the development of communication networks along the right-of-way, it eventually felt pressure from the growing automobile industry in the early twentieth century.

On this high note, the Reichsbahn entered the period of WWII and was quickly absorbed into the National Socialist agenda. The DB museum describes this period: Just a few years after the [national] socialists seized power in 1933, the Reichsbahn had already become a tool of the Nazi dictatorship. The employees were brought into line by means of systematic dismissals, massive propaganda, and ruthless intervention in the corporate structure. The Reichsbahn was now obliged to fulfill additional tasks, ranging from job creation schemes to organizing the “Kraft durch Freude” (strength through joy) holiday trips and providing basic logistic support for the mass rallies of the Nazis. This appropriation reached a climax when the state-owned railway was put directly to use in World War II to perpetrate the crimes of the Nazi regime. Neither the war of extermination in the East nor the deportation of millions of people to the concentration and extermination camps would have been possible without the Reichsbahn.

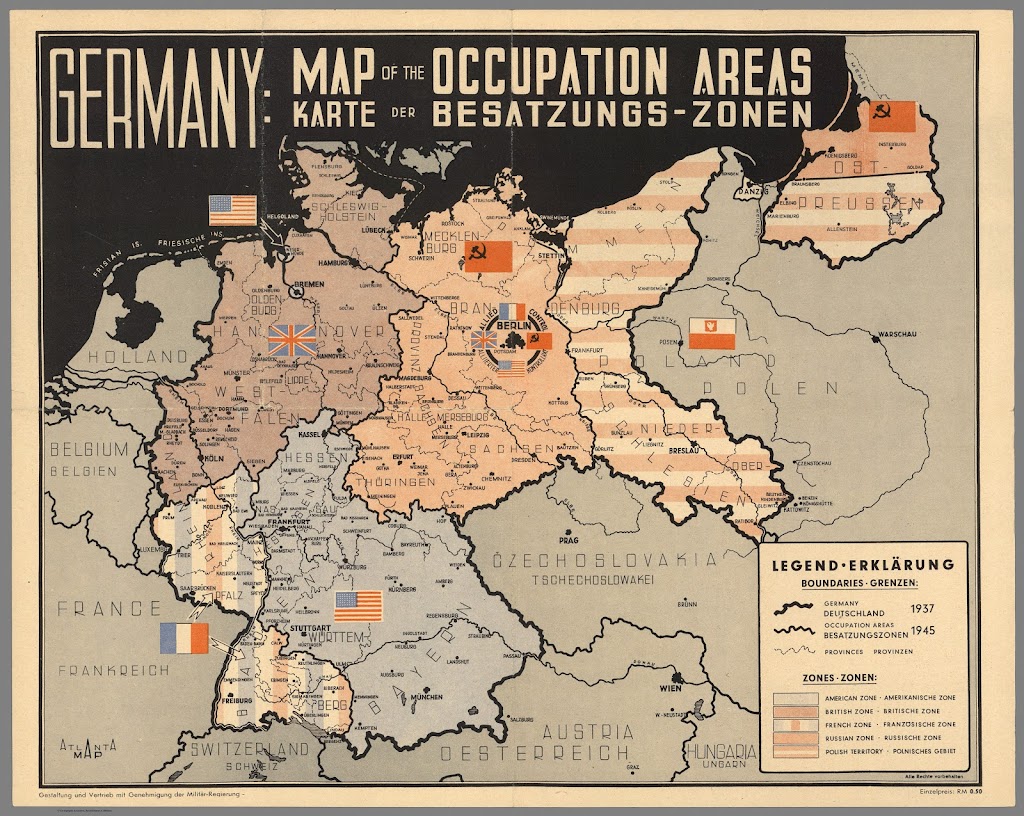

At the end of the war, the German Empire was divided into four separate zones controlled independently by the allied forces: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union. By 1949, the French, American and UK divisions in the western part of the country were consolidated as the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), or the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (BRD). The railways in the BRD were consolidated under the new name of Deutsche Bundesbahn. The zone controlled by the Soviet Union was renamed as the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), or Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR). The railways in this zone continued to operate under the national railways’ previous administrative title of Deutsche Reichsbahn.

The period of separation lasted until German reunification in 1990. During this time, the growth and development of the railroad network took two different paths under the governance and economic policies of East and West Germany.

The post-war political separation of the country encouraged the development of

north-south routes.

In the beginning, substantial work needed to be undertaken in both East and West Germany to repair war damage. East Germany was politically isolated and was therefore plagued by lack of resources, including elements for the production of iron and steel, appropriate materials for structurally sound concrete, and ample supplies of coal to produce steam power. The Reichsbahn shifted briefly to the production of diesel locomotives until the oil crisis of the 1970s, after which it labored to electrify its railway lines. Although the Reichsbahn faced developmental hardships, its passenger base was assured due to the lack of other available transportation methods in East Germany. Personal automobiles were rare; there was a long wait to purchase one, and parts used for repair were scarce.

The Bundesbahn in West Germany did not face the same shortage of resources as East Germany, because of its participation in the global market. Still, the Bundesbahn faced steep competition from the car, which at the time was an important symbol of freedom and modernity and coveted by the population. In addition, for social welfare reasons the ticket prices remained quite low, hindering potential profits. Through the late twentieth century, only one new line was constructed in West Germany, while most services were offered on the existing nineteenth century network upgraded for electrical power supply. Because of the high quantity of freight transported from the northern ports, and the limited opportunity to connect east/west across the inner border, investments were focused on the north/south routes across the state. In 1971, the first intercity (IC) services were offered and eventually expanded from first class only, to hourly service at all class levels.

and at the border in Berlin. Tracks stop at the border of American sector of

Berlin in this photo taken on August 26, 1961. Beyond the fence, in

communist-ruled East Berlin, the tracks have been removed. Source: AP/Worth.

The commencement of the TGV high-speed rail services in France in 1981 spurred a comprehensive plan for high-speed rail in West Germany, with the first lines constructed from Hannover to Wurzburg before reunification. Even with modernization and expansion of services, West Germany's share of intermodal transportation decreased from 1950–1990: 37% to 6% for passenger services, 56% to 21% for freight.

For both East and West Germany, the cold war was a time of limited network growth. In Japan (and later in France), high-speed rail reinforced the pre-existing hub-and-spoke territorial organization and compressed the scale of the nation into the scale of the city. In post-war Germany, the greater railroad network was severed from Berlin, its de facto hub. Thus, the network reorganized around a more dominant north-south axis and strengthened its polycentric network characteristics, compressing the boundaries of individual cities into each other.

border. At the insistence of East Germany, these links were decommissioned and

only eight heavily-guarded rail crossings remained. Even so, crossing the

border was an everyday occurrence as West German and military trains had

right-of-way access to West Berlin.

Although it was difficult for East Germans to leave the country, over time visits from Westerners and West Germans to the East were allowed with special visas. The two railroad administrations had to productively interact for this to occur, with changes of train crews at each crossing and collaboration over timetables. Local transportation in Berlin faced similar challenges due to the political separation of the city as well.

Reunification

in 1990 offered a unique opportunity for the railroad in Germany. Although

independently the Bundsbahn and Reichsbahn were both struggling financially,

the newly unified government saw an opportunity for reform as the two states

merged. As east-west transportation across reunified Germany became possible,

an influx of freight and passenger demands across Europe were expected.

Sensitivity to environmental issues was at a peak in the late twentieth

century, which also added to the potential for success. Railroad reform

involved changes to the constitution, seven new laws and more than 130 other

legislative changes. At the end, the two railroads consolidated and Deutsche

Bahn AG emerged as a joint stock company with an entrepreneurial approach to the

business of transportation.

The

contemporary high-speed rail system in Germany is heavily informed by the

specific development conditions of the politically un-united Lander of the nineteenth

century, the outcomes of the two World Wars in the early twentieth century, and

the cold war at the end of the twentieth century. When the newly formed

Deutsche Bahn AG began to plan for new high-speed rail services, it did so

within the established trend of convenient inter-city services to a region of closely-knit

mid-size cities. While investment had been made to north-south routes and

freight was an important generator of revenue, the east-west connections were

in poor repair.

Unlike

France, in which most high-speed lines are dedicated and connect Paris with

second tier cities with few intermediate stops, or Japan with its completely

dedicated network connecting second tier cities to Tokyo, in Germany the system

is almost always blended with commuter and freight services, and the schedule

makes stops at most mid-size cities. Even though portions of the system operate

at high speeds, the German system is much slower on average than either the

Japanese or French systems. However, German cities have better connectivity

with neighboring cities due to the polycentric nature of the network.

Whereas

France and Japan, with their respective hub-and-spoke network organizations,

challenge traditional notions of scale by collapsing the size of the nation to

the size of the city, the German high-speed rail network establishes more

profound city-city connections. Although traversing the entire country is still

rather time consuming, getting from one city to another within the same region

is quite easy. In addition, the design of the stations focus on inter-modality

with local bus and streetcar routes making it easy to get to a final

destination. The high-speed rail network in Germany is more like a very

comprehensive intra-city subway system that just happens to connect the whole

country. This network design is in response to, but also reinforces, the

settlement patterns of the country in which a multitude of mid-size cities

agglomerate to form substantial conurbations and regional politics demand HSR

stations in most cities.

2.2.4

City//City: China

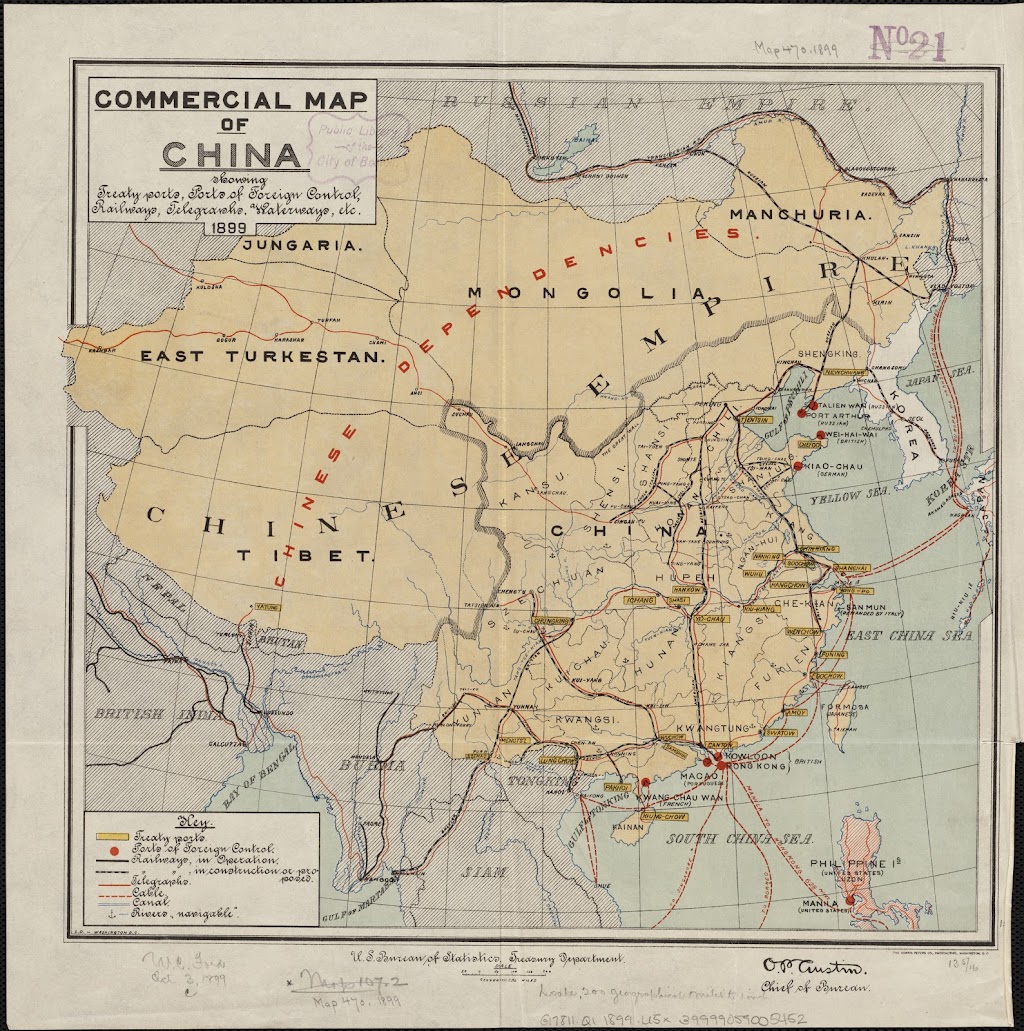

China’s railroad network developed in fits and starts at the end of the nineteenth century. Like Japan, China was initially wary of the new technology and, indeed, of the Westerners promoting it. In 1864 and again in 1876, the Qing government dismantled operational railroads constructed by the British and Americans, respectively.

The

first successful railway was dedicated to coal transport, and located in Hebei

Province in 1881. However, significant development of railroads did not really

commence until Chinese defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War when the

government realized modernization was necessary. Pressure from foreign powers

resulted in the large-scale construction and operation of railroads by the

British, American, French, Belgians, Germans, and Russians. The first domestic

railroad was constructed from Beijing to Zhangjiakou, and by 1911 there were

almost 5,600 miles of railroads in China. Most of these conventional routes

established Beijing as a hub, extending out into the rural country to the

north, south, west, and to the port city of Tianjin to the east.

Public sentiment never caught up with the need to modernize, however, and displeasure over a government ambition to nationalize the routes was a major motivation of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, leading to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. At this point, the new administration appointed Dr. Sun Yat-sen, a revolutionary and a planner, as the Director of National Railway Planning. Over the next few years, Sun Yat-sen developed and promoted an ambitious transportation and economic development plan for China (which included Mongolia at the time) that would rely heavily on foreign investment for completion. He viewed railways as the key to China's economic development, and railroad construction in the United States could provide an appropriate model for China. In a 1912 speech, Sun noted that the American railway network was 200,000 miles in length. (China's network at that time was only 5,600 miles.) Since China was five times as large as the United States, logic dictated that they needed a million miles of rail lines.

Internal

chaos and invasion by the Japanese hindered continuous rail development until

the 1940s. But Sun Yat-Sen’s vision remained a planning influence for many

decades, and some claim even the contemporary high-speed rail network owes much

to this plan. China doesn’t have what might be called a “National

Transportation Strategy.” Instead, the modern development of the railroad

started in 1949 with a series of Five Year Plans produced by the Ministry of

Railways that outlined specific development goals for the network. Lines were

expanded and modernized, but by 1990 demand for freight and passenger service

still far outstripped supply in most areas.

Part of the reason for this is China’s ever-growing demand for energy, and in this case the dominant fuel source is coal. Mining capacity has been called the first bottleneck to adequate power supply. Freight transport capacity is the second bottleneck. Other long-distance freight products important to the national economy include raw materials for factory production, such as coke, metal ores, iron and steel, petroleum products, grain, fertilizers and other bulk products. Freight rail has approximately 60% of market share for inland transportation. In order for China’s economy to continue to grow, both of these bottlenecks would need to be relieved.

Mining capacity has been called the first bottleneck to adequate power supply. Freight transport capacity is the second bottleneck.

To begin, the government commenced several rounds of “speed up” campaigns to improve speeds on existing routes throughout the country. Five rounds of upgrades from 1993 to 2004 improved passenger service on 4,800 miles of existing track, which were upgraded to reach speeds of 100 mph. A final round in 2007 brought 155 mph service to approximately 263 miles of track, and 124 mph service to a further 1,865 miles of track.

Critical to the plan was the goal to create more capacity for both freight and passengers through a separation of services by building high-speed passenger dedicated lines (PDL) and an upgrade to strategic freight corridors.

In

2003, the government issued its Mid- to Long-Range Network Plan (MLRNP) to

address the persistent shortfalls of the transportation network through to

2020. Critical to the plan was the goal to create more capacity for both

freight and passengers through a separation of services by building high-speed

passenger dedicated lines (PDL) and an upgrade to strategic freight corridors.

Another important political goal was to connect all provincial capitals with a

population total over 500,000. The PDL network would consist of four

north-south routes and four east-west routes totaling 7,500 miles operating at

speeds up to 218 miles per hour, with an additional 12,500 miles of mixed

traffic high-speed lines upgraded to 200 km per hour. The MLRNP also specifies

three key regional conurbations for transportation development: the Yangtze

River Delta region (Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou); the Pearl River Delta region

(Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shenzhen); and the Bohai Sea Ring (Tianjin, Beijing,

Qinhuangdao).

Although

the network is presented as a grid, it may be useful to view it as a series of

corridors in response to population and resource distribution. The population

of China is concentrated in the south and east along the coast, as are the

important conurbations of Bohai, the Pearl River Delta, and the Yangtze River

Delta. The north-south lines might be seen as primarily connecting those

larger, more prosperous population centers as well as the industrial centers of

the northeast. The east-west routes, then, provide access to rural agricultural

areas in the west and far west, creating a stronger connection with resource

rich hinterlands such as the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The

combination of speed-up campaigns and the implementation of the MLNRP has

resulted in the world’s largest national railroad network. Like Spain and

Germany, a political desire to connect provincial capitals influences the

network design to some extent. The necessity to balance freight and passenger

traffic is similar to Germany (although in Germany, freight and passenger lines

are mixed causing the construction cost per mile of track to be exorbitant.)

Like France and Japan, China’s solution involves the construction of new

passenger dedicated high-speed lines.

Throughout

China the core railway function is closely monitored by the Ministry of Rail

(MOR) to manage the integrated and coordinated national railway system that is

branded as China Rail. The State controls the two key levers of investment

(through the MOR) and pricing (through the NDRC) and there is little or no

intra-rail competition in the system. This is perhaps inevitable given the

acute shortage of capacity that has persisted over the past two decades, but

such strong control at the top levels of government has its draw-backs for

customer experience: it is policy to concentrate traffic and operations towards

maximized throughput, rather than divide the market through competition.

Therefore, managers operating day-to-day services focus on asset productivity

rather than customer service. The experience of travel as a passenger on

Chinese high-speed rail feels more akin to rationing than a free market economy.

-

In

examination of the national high-speed rail networks of Japan, France, Germany,

and China, emphasis was placed on the notion that this technology challenges

the traditional scales of urban planning. In the case of Japan, the Shinkansen

effectively collapses the scale of the nation down to the scale of the city,

Tokyo specifically. Few parts of the country are more than an hour or two from

the capital, expanding practical commuting distance to the point where it can

be argued that the entire country has become one temporally extended city.

In France, a similar time-space collapse occurs with Paris as the hub. The geographic context is different, however, because the overall proportion of the country is not linear and the hub is well north of the country's center. It is quick and easy to reach the capital from anywhere in the country by hopping on a TGV, but connectivity between other urban centers is slower and more challenging. In other words, while the benefits of spatial collapse seem to be evenly distributed in Japan due to the proportion and relationships of the islands, in France there are many parts of the country that do not feel a proportional amount of benefit.

Germany’s

political history and the resulting polycentric high-speed rail network

exhibits the collapse of boundaries between multiple urban centers into

interconnected productive regions, rather than reinforcing connectivity to one

dominant city as in Japan and France. The ICE network is the backbone of

several scales of efficient German transit, connecting regional airports to

S-Bahns, local U-Bahns, streetcars, and even bicycles.

Each country exhibits some form of spatial compression, as result of the combined forces of technology, culture, history, and geography.

2.3

Territory//Human

As the train began to permeate western culture in the late 1800s and early 1900s, writers, artists, and philosophers gained a potent new topic to analyze and discuss: the train shattered previous conceptions of space through the increase of speed. In 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, leader of the futurist movement, wrote in his manifesto, “Time and space died yesterday.” With these poetic words, he asserts that time is no longer a metered and inexorable progression, but rather a medium shaped and manipulated by technology.

[[slider id="231"]]

This was a cause of excitement for some, and of lament for others. As railroad historian and philosopher Wolfgang Schivelbusch recounts, “That in-between space, or travel space, which it was possible to 'savor' while using the slow and work-intensive eotechnical form of transport, disappears on the railroads. The railroad knows only points of departure and destination.” This optimism wasn’t shared by all. “They...only serve the points of departure, way stations, and terminal, which are mostly at great distances from each other,” writes an anonymous French author in 1840, continuing, “they are of no use whatsoever to the intervening spaces, which they traverse with disdain, providing them only with useless spectacle.”

Indeed,

much has been written (usually with a sense of foreboding) about the changing

role of the territory with the advent of new train technologies, both in the nineteenth

century and the twenty-first century. Geographer and professor Eric Sheppard

likens the changes in positionality wrought by ever increasing speeds to the

phenomena of a wormhole. “The relationship between positionality and physical

distance is complex. Positionality often leaps across space and thus cannot be

read off easily from conventional cartographic images of relative location. I

find the wormhole to be a useful metaphor for capturing this complexity. When

two relatively isolated places become closely connected, meaning that their

positionality becomes closely interrelated, then a worm-hole opens between

them.“

“It's not getting from A to B. It's not the beginning or the destination that counts. It's the ride in between...This train is alive with things that should be seen and heard. It's a living, breathing something -- you just have to want to learn its rhythm.”

David Baldacci

While

it is true that trains, especially high-speed ones, forge new temporal

connections between cities and collapse traditional scales of planning, the use

of the worm-hole as an analogy is misleading and overlooks the unique physical

parameters, sequences and processions, and unique spatial implications of every

transit mode. Travel has unique physical and temporal parameters depending on

the technology. Jets and airports foster different spatial experiences and have

different spatial implications than a train and a train station, or even a car

and a highway.

Trains connect the human scale with the territorial scale in important ways that, because of their specific technological parameters, cars and planes do not. The spatial implications of high-speed trains will be further unpacked throughout the remaining portion of Part 2, but here I will focus primarily on the affective qualities of the train in motion in specific geographic contexts, and secondarily on the physical parameters of the train itself and how those parameters mediate the experience of the territory. Like the futurists, I will use representation as a tool to investigate this relationship of the human and territory at speed.

Amtrak Southwest Chief

Somewhere near Odessa, Texas. March, 2015.

A train ride is not a road trip. In a car, territory is encountered and traversed frontally. The subject is usually a driver, is in charge of the route, and has responsibilities for alertness. The route is an asphalt strip accommodating moment-by-moment route adjustments. The vector of movement is in alignment with the direction of a person’s gaze, like walking—one foot in front of the other.

On a train, territory is experienced laterally and peripherally through a window to the right or left, viewing out the sides of the train car. The subject is usually a passenger with limited responsibilities, the rail and track a restricted substitute for the spontaneity of asphalt. Territory is confronted perpendicular to the vector of movement, and the windows continually reframe the landscape.

The plane of the train window and the line of the rail are the primary mediating geometries of the train.

De

Certeau insightfully describes these primary mediating geometries of the train,

stating, “Between the immobility of the inside and that of the outside...a slender

blade inverts their stability.” The blade he refers to is the train window, and

the double immobility (passenger and landscape) is resolved by the rail itself.

The plane of the train window and the line of the rail are the primary

mediating geometries of the train.

The

Southwest Chief, like most long-distance Amtrak trains, is a double-decker with

coach seats, café car, lounge car, and sleeper cars. The speed is slow, even

lumbering as compared to the high-speed trains of Europe and Asia. The

landscape through Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas is dry and vast, though not

barren. The sunrise is pink and yellow, the sunset deep blue and orange. For a

stretch near Odessa, the train clings to the national border and Mexico is

clearly visible. Although there is no physical boundary between the countries (besides the Rio

Grande),

the change in urban form and material at the border is significant: on the US

side, the structures are sturdy masonry. On the Mexico side, sheet goods and

corrugated metal dominate.

Shinkansen Tokaido Corridor

Somewhere near Tokyo, Japan. July, 2014.

“Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the Shinkansen.”

This calming phrase inaugurates every Shinkansen journey, and each station stop is heralded by a cheerful musical jingle. The conductors whisk efficiently through the train, pausing at each entry and exit for a brief bow to the passengers. The ride is smooth, punctuated by the occasional darkness of tunnels. In Japan, the train is ensnared by topography: mountains to the north and oceans to the south bracket most of the routes. The train seems to ricochet between these two boundaries, occasionally being swallowed up by the terrain into dark tunnels like the throat of some sleeping dragon.

The

experience of riding a train—the combination of the line of the rail, the plane

of the window, and the removal of responsibility for motion from the individual—has

been described by many with both fondness and curiosity. Author James McCommon

describes this phenomena as “train time” and likens it to a sort of waking

restfulness, while author Tom Zoellner calls it “train sublime,” stating that

trains:

“[H]ave the power to invoke odd spells like this...the tidal sway of the

carriages, the chanting of the wheels striking the fishplates...the glancing

presence of strangers on their own journeys, wrapped in private ruminations.”

TGV LGV1 Corridor

Somewhere near Lyon, France. June, 2015.

France was the second nation to adopt high-speed rail. Given its success in the country, it is no surprise that the TGV has become a national symbol of France. The TGVs are not as roomy as the Shinkansens or even the Amtrak Superliners, but they are still more accommodating than an airline seat. The café cars are lively and offer excellent* wine, cheese, and chocolate.

The topography of France, as compared to Japan or Spain, is relatively flat and the LGV routes are remarkably straight. Many of the busiest routes employ double-decker trains to accommodate the huge demand for travel. The TGV experience, especially from the second level, is of the train cutting a quiet, consistent slice through the mostly agricultural landscape, which is visible for miles beyond the window. There very few tunnels or viaducts. The sense of speed is communicated mostly through a quiet humming of wheels on rail. Conversations on the TGV are mostly muted, perhaps because of the lulling effect of the humming wheels.

A

passenger in a train may, at times, feel like the audience at a movie: the

scene outside the window shifting like frames in a reel of film. But a train

ride is not a movie. The passenger is still, the landscape is still, and the

film effect is created by the speed of the train, which constantly reorganizes

the relationship between viewer and viewed.

*At least to my American palate.

AVE Madrid–Barcelona Corridor

Somewhere near Tarragona, Spain. June, 2015.

Spain is aggressively constructing high-speed rail throughout the country. Although the network is incomplete, demand hasn’t quite caught up with supply and many of my train rides were only half full. The trains and the stations are shiny and new. (On one trip a group of raucous, drunk businessmen insisted I join them for dinner back in Madrid while the conductor looked on apologetically.) Spain’s topography is much more dramatic than France, so the AVE alternates between frequent short tunnels and low viaducts over expansive desert views.

Although

the train exists within the territory, it also defines its own distinct space from

the territory: a moving island within an ocean. The space of the train is

highly ordered, each seat numbered, each passenger ticketed, with limited

freedoms or the necessity for individual spatial negotiation. This schism of

independent space in motion, within an existing territory, challenges the

typical singular, static relationship of human to place. The passenger belongs

to both the space of the train and the place of the territory.

CRH Qinghai Railway

Somewhere near Lhasa, Tibet. August, 2015.

The Qinghai Railway in Tibet is technically not a high-speed route, yet it is the highest elevation route in the world. Both the tracks and the rolling stock are specially engineered for the higher elevations and to accommodate the extensive areas of ecologically sensitive permafrost along the route. Much of the line is constructed as a viaduct with columns extending deep into the earth. Where not elevated, the track is built on a tall, ventilated granite embankment that is shielded from the sun with shading panels. “Cooling sticks,” long pipes filled with ammonia pierce the ground below the embankment. As temperature increases, liquid ammonia becomes gas and pulls heat from the ground, cooling the substructure. Global warming threatens the entire line, as a consistent increase in temperature of just one to two degrees Celsius could destabilize the permafrost. The rolling stock is oxygenated, increasing the oxygen level from 21% to 24–25% to mitigate the effects of hypoxia.

Much of the route is captured in a narrow valley between the Tibetan mountains. Because the topography is so steep, there is much activity that happens in this valley. A river winds its way through, flanked closely by agricultural fields. A highway and the train line skirt the edge of the mountains on the opposite sides of the valley. The elevated position of the train, on embankment and viaduct, lend a unique perspective through the compressed valley.

ICE Frankfurt–Cologne Corridor

Somewhere near Frankfurt, Germany. July, 2015.

In Germany, the organization of cities is relatively decentralized. Rather than one large, dominant capital city such as in France and Spain, Germany has many medium-sized cities that form larger urban agglomerations. Still, the distinction between urban and rural is quite pronounced, with little of what Americans know as “suburban sprawl.” The train connects city-center to city-center, but in between it slips passed tight groups of houses and wide agricultural fields. As author Ruth Levy Guyer describes: “Trains go where cars cannot: into canyons, along rivers, through mountains, sidling up to back yards and into town centers.”

2.4

Territory//Station

High-speed

trains have gotten faster, but are still strikingly similar in form and

function to conventional steam trains. George Stephenson, the Englishman

responsible for large-scale implementation of the railroad in the early nineteenth

century, would recognize high-speed trains if he were alive today. Trains still

involve all the conventions and processes that have existed since the

beginning: the purchase of a ticket, the departure from a platform in a

(usually large and architecturally significant) train station, a ride in a seat

with the landscape sliding passed from left to right in a window. The train

still runs on rails attached to sleepers on a layer of rock or gravel ballast.

Travelers are still welcomed in stations by relatives and friends, usually

right on the platform.

Clearly, high-speed rail has much in common with its steam and diesel ancestors. So the question is then, Has HSR made a significant spatial impact beyond the existing impacts of the conventional railroad? Yes and no. Some of the spatial implications are new, and have to do with the train and its integration with contemporary modes of transit (such as airplanes and cars) or contemporary urban organizations (suburbs and edge cities). Other implications are simply amplifications of conventional impacts. For example, a new train station was always a boon for a small town, focusing growth and activity at the station. But the intensity of urban development planned around new stations today is unprecedented.

Moreover, the engineering of the tracks and the routes for high-speed trains is more complicated than conventional trains. The high speeds require the routes to be as straight as possible, and for any curves to have extremely large radii. Elevation changes are undesirable yet achievable with higher energy input. Because speed is such an important consideration, and construction costs per mile are high, even small reroutes for stops in smaller towns are often highly contested. These technical limitations, along with the high cost of constructing stations in existing cities, have led to HSR station development in peri-urban or non-urban sites.

This section uses specific case studies to document the roles of HSR station development (in various locations relative to urban centers) in the organization of a territory. This list of cases is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather to highlight a variety of examples.

2.4.1

Historic Urban Center

In some cases, stations within historic urban centers are modified to accommodate high-speed rail service. At times the station is almost entirely re-utilized with little modification, at others only a small portion of the historic station remains. The advantage of reusing central city stations is the location: direct downtown connection. The disadvantages include the technical complexity of expanding rail corridors, or developing the station area with other land uses (like hotels and office space) that are compatible with HSR stations.

The following case studies highlight several examples of station development in historic urban centers.

[[typology id="241"]]

2.4.2

New Urban Center Stations

A new urban center station is characterized by substantial city development around an HSR station where there was previously minimal development. Often these cases take advantage of decommissioned military sites or formerly industrial sites: locations that are near the historic city center, with large parcels for HSR friendly development and few stakeholder groups that might be negatively affected by development. It is commonly held that HSR stations, in and of themselves, are not capable of producing a new urban center. Rather, successful new urban centers are created only when new stations are accompanied by reciprocal investment in local transit, economic development, housing, hotels, etc.

The following case studies note the development scenario in which HSR was one factor in creating a successful new urban center.

[[typology id="242"]]

2.4.3

Urban Periphery Stations

Given the complexity of locating HSR stations in dense urban environments, sites on the edges of existing cities are sometimes selected for station development. When these sites are designed with a good urban framework, an appropriate mix of land uses, thoughtful consideration of site opportunities and limitations, and good public transit, these types of sites have the potential to develop into viable neighborhoods or new centers.

The following case studies highlight HSR stations that have been sited at the periphery of a city (with varied results).

[[typology id="243"]]

2.4.4

Suburban Stations

Usually,

when we think of a journey by train (high-speed or conventional), we think of

zipping through the countryside passed farms and crops and tiny houses dotting

the landscape, arriving at our destination firmly inside a city center. We

don't imagine stopping in the country, let alone in a suburban environment. But

contemporary HSR stations have been developed to address a wider range of

scenarios than just the city, inventing new station typologies to accommodate

contemporary urbanization patterns.

The following case studies highlight HSR stations in suburban environments.

[[typology id="244"]]

2.4.5

Rural Stations

A

unique term for rural stations was coined by the French:

la gare betterave, which translates directly to “beetfield station.”

In other words stations located in the middle of nowhere. There are many

reasons that HSR stations would be located in a rural setting: less overall

route deviation means faster connections between major cities; upgrading or

expanding rail corridors in existing cities is often complex and costly; and land

acquisition for complementary development around a new station is more

difficult inside a city. Given the auto-dependent nature of the built

environment in America, access to more rural locations could require stations

similar to those presented here.

The following case studies document HSR stations in rural locations.

[[typology id="245"]]

2.4.6

Suburban//Urban Networked Stations

When developing an HSR network, one of the first major considerations is the station location. Centrally located urban stations offer convenience, while peripheral or suburban stations offer lower construction costs and fewer development difficulties. In most European and Asian examples, central city locations offer the most access to the greatest number of potential travelers. But in the US, where a greater number live in suburbs, that may not always be the case. Traditional development patterns suggest that successful rail development should address both conditions, urban and suburban, in the design of an HSR network.

In the following case studies, a central city station and a suburban or periphery station work in tandem to provide access to both urban and suburban populations.

[[typology id="246"]]

2.4.7

Airport Stations

High-speed rail is often advertised as an alternative to air travel. However, in both European and Asian precedents, stations have been incorporated into (or near) new and existing airports. In these cases, HSR has been used to establish intermodal hubs, to complement international or long haul flights, and to increase airport access throughout a given region. Most HSR airport stations present themselves simply as stops along a given route, while in other cases direct HSR links have been specifically developed to connect a major city to an airport.

[[typology id="2471"]]

[[typology id="2472"]]

2.5

City//Station

2.5.1

Urban Station Typologies

There

are two broad categories, or typologies, of urban train stations: terminal

stations and through stations. A

terminal station is a structure that is

positioned at the final destination of a railroad and is more typical of historic

train stations. The structure is often a grand, cathedral-like building with vaulted

ceilings and train platforms right at street level. You can step off the train,

slip through a bustling station, across a plaza, and right into the heart of

the city.

Over