Part 3

I Hear that Train A-Comin'

Speculations on High Speed Rail in America

As a platform for speculation, Riding the Rails can inform the future of high-speed rail in America. To that end, Texas has been chosen as a case study. This section explores the history of high-speed rail in Texas, and considers the current development of a privately funded route from Dallas to Houston.

3.1

A Brief History of High Speed Rail in Texas

"In general, man does not know where he is going, but he wants to get there as fast as possible."Roman Guardini

Of all the

territories suited to high speed rail in the United States, the flat, arid

landscapes of Texas are among the most promising. Although the state is vast,

much of the population is focused in just a few metropolitan regions in the

eastern half of the state. These cities are, at their farthest, less than 200

miles apart, which fit neatly inside the high-speed rail “sweet spot” of

distances greater than 100 miles but less than 500 miles. The auto-dependent

culture lends itself to considerable traffic delays, adding a significant

amount of time to long-distance trips. Future population growth is predicted to

be higher in cities than in suburbs, providing increased ridership potential.

Finally, the largest cities in Texas are part of an economically co-dependent

network often called a “Mega-Region.” Business ties are strong between these

cities. These factors combine to make a good case for the development of high-speed

rail.

Short-haul flights between Texas' largest cities are in high demand. Source: Author.

Because of the economic entanglement of cities and the large expanse of the plains, Texas actually has a longer history with HSR than most states and has debated implementation since the late 1980s. At that time the state legislature directed the Texas Turnpike Authority to create a report outlining the feasibility of high speed rail service in the “Texas Triangle,” including Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin. The results were favorable and the report advised further consideration of HSR. The legislature followed the advice of the report and created the Texas High-Speed Rail Authority in 1989 to oversee and regulate high-speed rail ventures in the state that, by law, would be privately funded. As stated clearly in the bill, “It is not in the public interest that a high-speed rail facility be built, financed, or operated by the public sector."

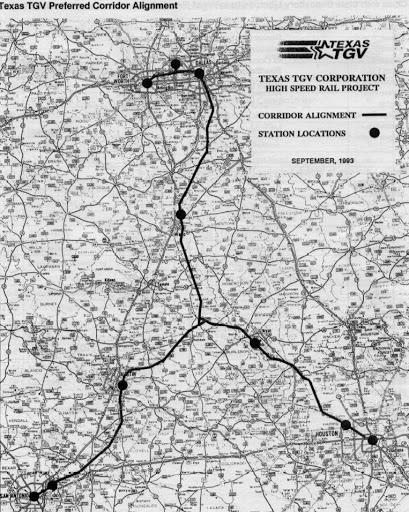

Soon after the creation of the High-Speed Rail Authority, two groups applied for franchise consideration: one using French TGV technology and the other using German ICE technology. The “Texas TGV” consortium was eventually awarded a fifty-year franchise in 1991 with their ambitious “T-Bone” master plan linking all the major cities in Texas. But the Texas TGV was not to be for a variety of reasons.

Public sentiment turned against the technology, and Southwest Airlines (which stood to lose a enormous revenue from their short-haul intrastate flight services) led an aggressive campaign against high-speed rail. But the ultimate downfall of the Texas TGV was financing. As stated by the Texas Tribune, “Some 70 percent of the project’s $6 billion price tag would be provided via tax-exempt private activity bonds, more than federal law allowed a company to borrow using that type of financing. The venture hinged on Texas TGV changing federal law to ease the restrictions.” Although a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) had already been completed including ridership studies suggesting a private franchise could be solvent within a few years of operation, the franchise was revoked when it became clear that federal law would not be changed and other financing was not available for the project. A year later the state abolished the Texas High-Speed Rail Authority and its functions were not absorbed by any other state agency. In Texas, high-speed rail was dead.

Federal funding for rail have always lagged behind investments in air and rail. Source: Author.

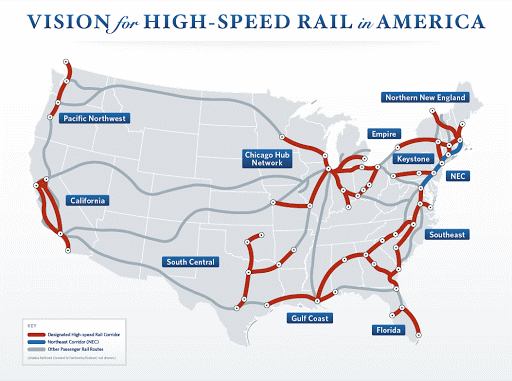

Hope vanished until

the late 2000s when national interest in passenger rail was renewed with the

federal Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA) of 2008. The

PRIIA directed each state to establish or designate a state rail transportation

authority and develop statewide rail plans, including both passenger and

freight rail. These state plans would inform the national

Vision for

High-Speed Rail in America

, created by the Federal Railroad Administration

under the direction of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of

2009.

In Texas, the national vision includes a generous corridor that extends from Tulsa to San Antonio, from Dallas to Arkansas, and along the gulf coast from Houston to New Orleans. Source: FRA

The national vision in and around Texas includes a generous corridor that extends from Tulsa to San Antonio, and another along the gulf coast from Houston to New Orleans. Both federal bills include grant funding for planning and development work: the ARRA budgeted 8 billion for intercity passenger initiatives, with priority for high speed rail projects in the designated corridors outlined by the national Vision for High Speed Rail. By 2010, the nation had both a vision and a funding mechanism for planning and corridor development.

As a result of past interest in high-speed rail and new federal funding opportunities, Texas has both public and private organizations working on three separate corridor studies for HSR. In 2011 the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) was awarded a $15 million ARRA grant for preliminary engineering and NEPA studies for high-speed rail between Dallas/Fort Worth and Houston. (NEPA is a process of fact gathering, alternatives evaluation, and public outreach that results in an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and a Record of Decision (ROD), which allows an infrastructure project to be developed.) In 2012, a private group called Texas Central Railway (TCR) made a proposal to TxDOT to study and develop only the Dallas-Houston portion of the corridor. TCR is a consortium of private investors working with Central Japan Rail towards incorporation of proprietary Japanese Shinkansen technology, and has emphasized that they intend to develop the corridor using only private funds. As such, a division of labor was created in which the FRA and a private consultant, with support from TxDOT and TCR, are leading the NEPA process on the Dallas-Houston corridor as a stand-alone project. To date, they have been successful through several stages of the NEPA process and a draft EIS is expected in 2016.

Multiple high speed rail studies are being conducted simultaneously by the public and private sectors. Source: Author.

Separately, TxDOT is

leading the NEPA process for the Dallas-Fort Worth corridor through the creation

of the Commission for High-Speed Rail in the DFW region. TxDOT is also

currently leading a third high-speed rail study: the Texas-Oklahoma Passenger

Rail Study (TOPRS), which includes an 850-mile corridor from Oklahoma City to

South Texas via Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, and a few other cities. This

study is scheduled to conclude by the end of 2016 after the completion of a

service-level EIS and a service development plan. (At this point, it is assumed

that a private consortium could propose to develop the preferred route.) A

fourth passenger rail study is being conducted for commuter rail service between

Austin and San Antonio, though it is not expected to achieve the speeds

associated with high-speed rail.

3.2

Speculations & Provocations

[[gallery id="31"]]

Texas is a good case study for this research project because it offers conditions similar to the rest of the US, as well as idiosyncratic conditions specific to Texas.

Like most US regions, population density in all of the major cities is much lower than a typical European or Asian city. Diffusive urban organizations such as suburbs and edge cities are much more common than dense patterns of development, and driving into the city to catch a train is just as inconvenient as driving to the airport. Public transit is much less comprehensive, so getting around upon arrival by high-speed train is a challenge. There is already evidence of general NIMBYism towards the existing HSR studies, an unfortunate cultural tendency prevalent throughout the US. Then there are real and perceived cultural hurdles, such as the notion that Americans are just too automobile-centric to take the train.

Unique to Texas (and to some extent other politically conservative states) is the notion that the private sector should have a leading role in development. It is not uncommon for the private sector to have a major role in the development of bridges, highways, and other infrastructure that, in other states, is provided by the public sector. In fact the 1989 bill that created the first Texas High-Speed Rail Authority clearly stated, “It is not in the public interest that a high-speed rail facility be built, financed, or operated by the public sector.” If America is to construct an effective high-speed rail network, as I think it should, then these general and specific hurdles have to be addressed. The following speculations use information available from TxDOT, the FRA, and TCR, in combination with the research conducted in Parts 1 and 2, to speculate about the implementation of High-Speed Rail in Texas.

Although Texas has three HSR projects undergoing the NEPA process, the Dallas–Houston corridor being studied by Texas Central Railway, a private sector group, is the closest to becoming a reality. As an initial step TCR identified four general corridor options for review by the FRA, which identified one of those options as a viable solution. Next, TCR identified several specific alignment options within the viable corridor for review, as well as several station location options for Dallas and Houston. Because TCR is a private company, naturally the primary goal for design, construction, and operation of the line is ultimately a return on investment. The preferred station location in Dallas reflects the goal of profitability: a site at the edge of downtown on a vast greenfield for ease of station construction and the potential development of complementary uses.

TCR has identified two station locations in Dallas, though both locations are in the same general area near the convention center. Source: Texas Central Railway

As the previous research has shown, train stations have an incredible potential to create rich, vibrant, and diverse hubs of activity. Along with appropriate private and public investment, a train station can catalyze a new urban center, a new suburban center, or even help regenerate part of an existing city. It is an opportunity to correct the urban divisions created by the railroad in past centuries with innovative urban design and architecture. As cited by Amtrak, “A well-planned train station is one of the best investments a community can make as it seeks to expand its appeal as a place for tourism and business investment and also cultivate civic pride.” With so much potential civic benefit on the line, it is imperative that non-market driven factors are included in the decision making process for alignments, station locations, and HSR technology selection. The following provocations on station location in Dallas privilege civic goals and the common good in the station location process.

PROVOCATION #1

Urban Periphery//A look at Central Texas Railway’s Preferred Location

[[gallery id="32"]]

Given the complexity of locating new high-speed rail stations in dense urban environments, sites on the edges of existing cities are sometimes selected for station development. Recent examples include: Albacete in Spain, Avignon TGV in France, and Sudkreuz Station in Germany. These sites usually offer larger developable parcels (for parking and complementary uses) as well as less complex construction scenarios for the station and rail approach. The trade-off, however, is connectivity, because these sites are not easily accessed from the city or surrounding neighborhoods. Stations at the urban periphery should be designed with a robust urban framework, an appropriate mix of land uses, thoughtful consideration of site challenges, and excellent public transit connectivity. When successful, these types of sites have the potential to develop into viable neighborhoods or new urban centers. When unsuccessful, a station will feel isolated from the city, will experience low ridership, and will fail to generate any meaningful development in the surrounding area.

The location preferred by Texas Central is currently isolated by large-scale infrastructure: the I-30/I-35 canyon to the northwest, a railroad corridor to the northeast, and the future Trinity River toll road to the southwest. The key to successful development at this site in Dallas will lie in establishing good connections to existing public transit, to the Trinity River, to the Cedars neighborhood, and to the convention center.

Provocation #2

Urban Core

[[gallery id="33"]]

Like many American cities, Dallas is currently experiencing an urban revival. The city has made serious investments in a new light-rail network, streetscape improvements, and the pedestrian realm. The Arts District is flourishing with many new amenities. Connections to surrounding neighborhoods outside of the inner freeway loop have been planned and are beginning to take shape, starting with Klyde Warren Park, which creates a pedestrian bridge from the Arts District to Uptown across Woodall Rodgers Freeway. Private development is continually contributing new residential and commercial projects, and substantial urban growth in employment and population is expected by 2030. Dallas is becoming a diverse and vibrant city as a direct result of both public and private investment in the built environment.

Still, with all these improvements and momentum, there remain several pockets in the urban core with block after block of surface parking lots ripe for development. A new high-speed rail station located in the center of town would catalyze dense infill development within the inner loop. Routing the high-speed rail alignment through the center of the city would be costly, requiring tunneling under city streets. Yet the economic impact of new development in the center of town would benefit a wider variety of businesses, residents, and property owners than the individually owned peripheral site preferred by TCR. The connection to light rail and long-distance buses would be more convenient, and a properly sited station could activate the existing tunnel network and provide momentum for a better pedestrian connection with the Deep Ellum neighborhood.

The impetus for this

provocation is two-fold. First, that the civic benefits of a new high-speed

rail station should be harnessed to create a more vibrant city center,

privileging dispersed economic benefit and sustainable urban infill development

over peripheral greenfield development. Second, that train stations have a

unique ability to create a central hub of activity and to catalyze private

complementary development within walking distance. US cities are experiencing a

revival, but most still need considerable investment to achieve a successfully

dense mix of uses.

The opportunity to harness the “centering” ability of

stations shouldn't be overlooked. It warrants substantial public consideration

and, though not traditional in Texas, substantial public investment.

Case

studies for this type of project include Cordoba Station in Spain, Porta Susa

Station in Italy, and Part-Dieu TGV Station in France.

Provocation #3

Suburban/Urban Combo

[[gallery id="34"]]

Most important European and Asian cities have high population densities because people there live in cities more commonly than in suburbs. As such, trains that zip along from city center to city center are easily accessible for most passengers. In America, even in major cities, a substantial portion of the population lives outside the city center, in suburbs and “edge cities.” Although recently millennials and empty-nesters have been bolstering urban populations, in America the suburbs are here to stay. An essential task of American high-speed rail will be to balance the needs of urban and suburban passengers. It is illogical for a suburbanite to fight traffic all the way downtown, just to board a train headed back out of the city. Moreover, huge parking garages are not the highest and best use for urban property. (We won’t be able to get rid of all the parking, but our cities will be richer, experientially and in terms of tax dollars, when urban land can be preserved for commercial and residential uses.)

There are examples in Europe and Asia where a suburban high-speed rail station complements a main urban station. The two stations work as a pair, serving a greater range of passengers more efficiently than either station alone. At the urban station, parking is provided at nearby garages, while the station real estate itself is reserved for shopping, dining, passenger services, and sometimes added amenities like hotels or concert halls. These suburban stations are easily accessible by highway, offer plenty of parking, car rental, and connection to the greater region by public transit on bus or light rail. The high-speed rail tracks might be shared with high-speed commuter services, such as southeastern commuter service in the UK, or the right of way might be shared with conventional commuter rail on separate tracks.

In Dallas, sharing the HSR right-of-way with a new light-rail route will have the added benefit of addressing important equity issues. The alignment passes through a predominantly non-white area of south Dallas that is also devoid of public transit and employment opportunities. A new light rail will connect residents with the employment rich areas of Dallas north of the city and take more cars off the freeways. As the birthplace of both suburbs and skyscrapers, America is fundamentally a place of mixed development patterns. The challenge will be to provide service to both.

Provocation #4

Scales of Planning

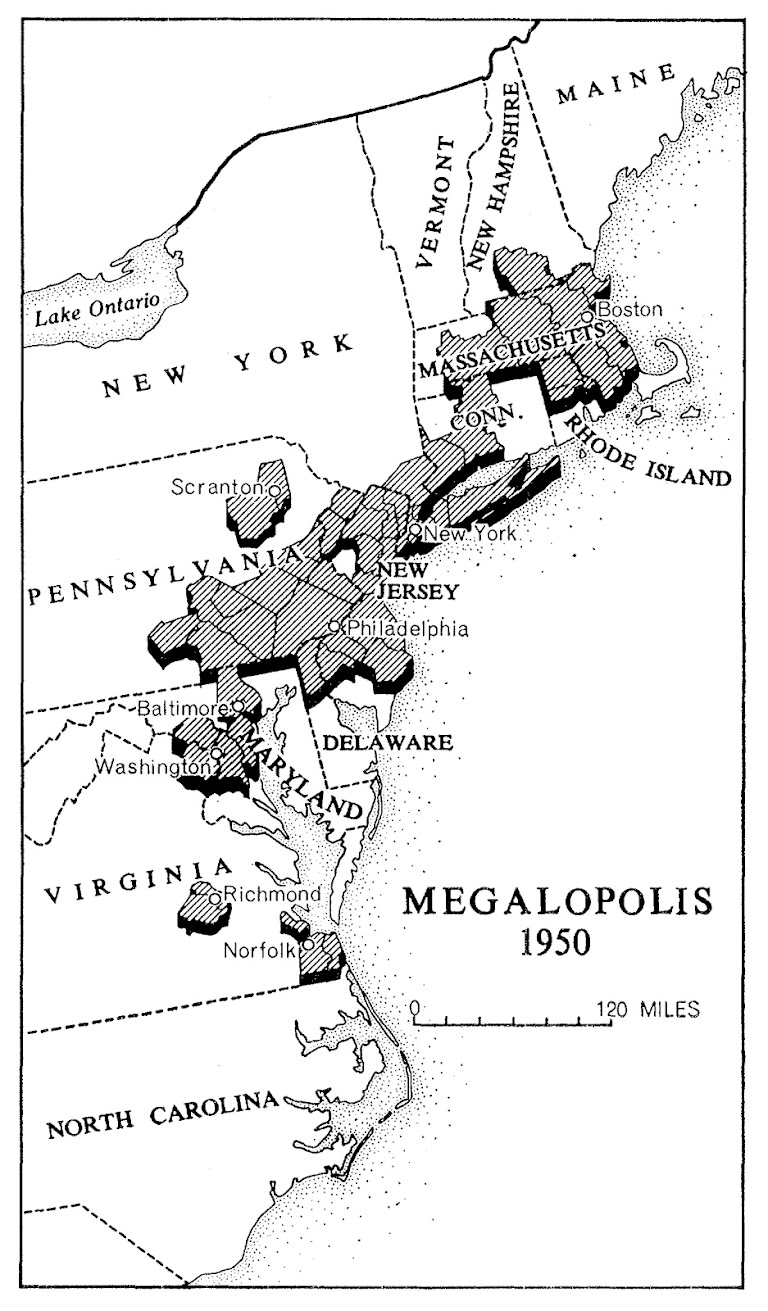

In the United States

and across the world, urban development over the last century has been

characterized by processes of spatial, cultural, technological, and economic

convergence known as globalization. Economies, ideas, and relationships have

become more interconnected and interdependent within a social space no longer

bound by the limits of distance. As early as 1910, Patrick Geddes coined the

term “megalopolis” to describe a pattern of development in which the growth of

relatively proximate cities causes them to merge and form urban agglomerations.

Considered as a single entity, a megalopolis or mega-region is a polycentric

organization of networked individual cities. An excerpt from “The Rise of the

Mega-Region” describes further:

Patrick Geddes' illustration of the BOS/WASH megalopolis.

[Mega-regions] perform functions that are somewhat similar to those of the great cities of the past—massing together talent, productive capability, innovation and markets. But they do this on a far larger scale. Furthermore, while cities in the past were part of national systems, globalization has exposed them to world-wide competition. As the distribution of economic activity has gone global, the city-system has also become global—meaning that cities compete now on a global terrain. Urban mega-regions are coming to relate to the global economy in much the same way that metropolitan regions relate to national economies[...]Mega-regions are more than just a bigger version of a city or a metropolitan region. As a city is composed of separate neighborhoods, and as a metropolitan region is made up of a central city and its suburbs, a mega-region is a polycentric agglomeration of cities and their lower-density hinterlands. It represents the new, natural economic unit that emerges as metropolitan regions not only grow upward and become denser but also grow outward and into one another. Just as a city is not simply a large neighborhood, a mega-region is not simply a large city—it is an ‘emergent’ entity with characteristics that are qualitatively different from those of its constituent cities.

This urban formation is directly related to advances in mobility technology, such as the high-speed train and the jet, and communications technology, such as the Internet and the proliferation of computers and smartphones, which provide for effective time-space compression. This pattern of urban development is growing. In the late twentieth century geographer Jean Gottman identified twenty-five such urban agglomerations across the world. Later, researchers utilizing global nighttime light emissions and other datasets predicted forty mega-regions with economic output of more than $100 billion that produce 66% of world output and account for 85 percent of global innovation.

[[slider id="31"]]

With federal legislation such as the PRIAA of 2008 and the ARRA of 2009 that encourage development of high-speed rail, the United States has taken an important step towards meeting the infrastructure needs of the twenty-first century. What is missing is a recognition of the mega-region in which high speed rail is applicable. Traditional scales of planning operate at the local, state, and national levels, but mega-regions exist in a scale above the boundaries of state planning, and below the efficacy of federal visioning. RPA has identified eleven distinct mega-regions in the United States, and Texas forms part of two: the “Texas Triangle,” which effectively extends into Oklahoma, and the “Gulf Coast,” which extends into Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia.

In recognition of the critical importance of the mega-region as a competitive economic unit, the federal government should create official planning agencies for each mega-region. These entities would work with each city in the network to create and implement a plan for economic development of the region along with transportation and infrastructure. In this way high-speed rail would be developed to promote accessibility to the entire region. (A domestic precedent for this type of agency is the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), while an international example is the European Union’s European Spatial Development Program (EDSP).) Private developers would have an important role to play, but within a larger planning framework that balances bottom line profit with the needs of the mega-region communities.

Provocation #5

Public vs Private Development

In Texas the private sector has an established role as a developer of public infrastructure. In Dallas alone several toll roads have been privately developed and the construction of a few bridges involved substantial private sector funding as well. Currently the highly contested Trinity Toll Road is a private development initiative. So in Texas it's not a question of if the private sector should be involved in high-speed rail development, so much as how. There are many examples of private sector involvement in high-speed and conventional rail in Europe and Asia. In 1991 the EU directed reform in the structure of national railways such that operations would be separated from the development and maintenance of infrastructure. This allows system growth to be directed by national and EU planning agencies, while also providing for healthy competition in operations. Services such as Eurostar, Thalys, Thello, Italo, Virgin, and many more operate internationally and compete with national trains such as the Spanish AVE, French TGV, and German ICE trains. Station and station area development has been leveraged with private investment: in Spain, private firm Vialia has worked with Adif to develop stations as shopping destinations, and in France, SNC partnered with private companies Klépierre and Spie Batignolles Immobilier to renovate Saint Lazare station and convert more than 100,000 square feet into eighty retail spaces.

In order for Europe to create a network traversable by trains across national borders, standardization and interoperability have been of utmost importance. Rail gauge (the distance between rails on the tracks) has been standardized at 4 feet 8 1/2 inches, and trains are designed to accommodate a variety of signaling technologies. For example, Thalys international high-speed trains (which connect Paris, Brussels, Cologne, and Amsterdam) are equipped with a minimum of seven different signaling systems for cross-border operation. Japanese Shinkansen technology, on the other hand, is not designed to accommodate or be interchangeable with other types of trains. Both European and Japanese technologies are safe and reliable. The public sector therefore needs to be involved in irreversible decisions about technology, because they affect the ability of the future system to be accessible by multiple operators.

The Texas state

legislature has embedded this statement into law, “It is not in the public

interest that a high-speed rail facility be built, financed, or operated by the

public sector.” This sentiment is shortsighted and ignores the enormous

benefits, to the community, of public/private development. High-speed rail

development should be aligned with American ideals of entrepreneurship,

equality, and accessibility, and as such the private sector has an important

role to play. But development of the system shouldn’t be seen as a burden on

the people. Rather, it should be seen as a public good, a tool to focus public

and private investment to create better cities, and a better network of cities

within the mega-region. Barring the public from involvement in planning and

development will limit the advantage of Texas HSR to a small cohort of

investors, in the form of profits, and restrict the potential for healthy,

dense, more vibrant city centers that benefit the community broadly. The difference

between the two is the difference between limited augmentation and revitalizing

transformation.